A recent deluge of videos on social media depicting evictions and acts of horrible mistreatment of Africans living in Guangzhou, China has sparked outrage among many and put a strain on relations with Beijing.

While this anger is legitimate and China immediately owes Africa answers and solutions, the dispute contrasts with a more complex reality – that Africa very much needs China to successfully rebound to kickstart their economies.

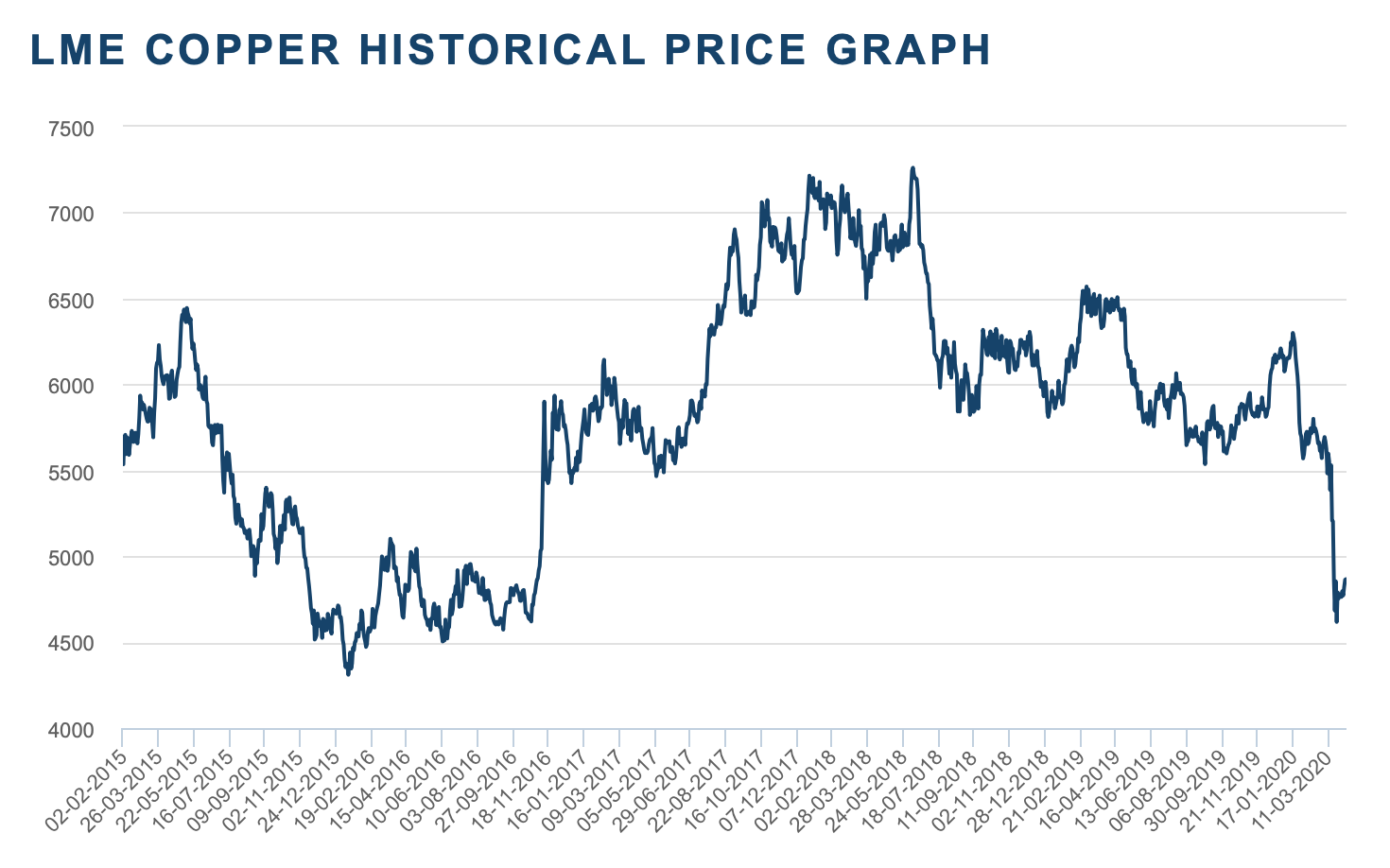

In the last month, the price of copper has fallen below USD $5000 a tonne for the first time since October 2016. With fears of a prolonged global recession resulting from the devasting impact of the coronavirus pandemic, on 19 March the copper price saw its largest one-day percentage fall since the 2008 financial crash.

As global demand dries up, the African countries dependent on minerals exports will be hit very hard. For Africa’s Copperbelt region – Zambia, the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo – the effect on their economies could be devastating. For example, copper accounts for more than 70 per cent of GDP in the DRC and more than 75 per cent of Zambia’s exports.

History would suggest that copper prices will recover with the resumption of global activity when COVID-19 related restrictions begin to substantially ease. Given that China is the world’s biggest consumer of industrial metals and consumes half the world’s copper, its economic revival is of particular relevance.

Indications that China’s economy has begun to return to some semblance of its pre-coronavirus state include its most recent PMI report. For the month of March China’s official manufacturing purchasing managers’ index rose to 52.0, after February’s record low of 35.7. Whilst this indicator does reflect an expansion in manufacturing activity, given the dramatic downturn in February the economy is still far from operating at full capacity.

Last week, Beijing published figures on the economy’s first-quarter performance showing the lowest gross domestic product growth in decades, the first contraction since 1976. Whilst the government may revise its economic growth targets for 2020 it reportedly remains determined to see growth “in a reasonable range” (in 2019 GDP grew 6.1%) in order to hit its goal of doubling the size of the Chinese economy between 2010 and 2020.

In the coming weeks or months it is therefore likely that, as Beijing attempts to turbocharge its economy’s recovery, we will see a wave of infrastructure spending in China. This in turn will aid the recovery of copper – essential for copper-dependent economies in Africa’s Copperbelt region and key Latin American suppliers including Chile and Peru.

There’s no question that Africa and China have become interdependent.

Africa’s Copperbelt region produces 70% of the world’s cobalt and a significant proportion of rare minerals such as lithium. In addition to copper, China is the largest importer of cobalt and other rare minerals, as it is the principal producer of mobile phones, batteries and other electronic components. Chinese-owned companies have also heavily invested in mines in the region – economic downturn in China has meant that these investments have slowed.

In Zambia, almost 30 per cent of sovereign debt is issued by China and 90 per cent of investments in infrastructure projects underway are funded by the Chinese government. Given such significant dependency on China, other foreign investors are in turn dissuaded from investing in Zambia when China has been hit hard economically.

For an already stressed economy such as Zambia’s, the additional strain of a sudden drop in demand for its main exports and a potential public health crisis could have serious real-life implications for large swathes of its population. The importation of goods, for instance, immediately becomes more difficult.

With USD $1.2 billion in reserves in the Central Bank as of March 2020, without any external stimulus Zambia would have less than six weeks import cover.

With the opposition pressuring the government to take an IMF loan which would be accompanied by devastating austerity measures, the eventual resurgence of copper once global activity resumes in earnest will be essential for Zambia to bring in revenue, grow its economy and enact policy to relieve its debt crisis.

It’s impossible to ignore the side effects of low commodity prices on development in Africa. Currencies are depreciating, making debt servicing more expensive and imports such as fuels and oil very difficult.

As demand for key mineral exports lags, so does foreign investment, so does infrastructure building, and in turn many states will find it difficult to create enough capacity to provide employment, not to mention the public safety costs of containing a deadly virus.

The longer and more severe economic downturn is in key ‘import’ countries such as China, the longer it will take for copper prices to recover. Equally, the longer lockdown continues in countries that China exports to including the current coronavirus hotspots of Europe and the United States, the less chance resource-dependent economies will have to avoid economic and potentially humanitarian calamity.

Copper will, eventually, rebound. Coronavirus is a finite event and global industrial activity will resume. This week, for example, construction and manufacturing companies were given the go ahead to return to work in Spain.

Furthermore, in the wake of economic crises there is a tendency to invest in large infrastructure projects. Such projects require significant quantities of copper. Infrastructure-led recovery in China, and indeed in Europe and the United States, would be good news for copper exporters such as Peru, Chile, Zambia and DRC and ROC.

The longer-term projections for copper are also promising. As the push for greener energy intensifies, so too might an increase in demand for copper. Solar and wind farms require copper cabling, fast chargers of Electric Vehicles require up to 8kg of copper each and the vehicles themselves contain approximately four times more copper than conventional cars. Unless new capacity stymies increased demand, copper prices are likely to be steady in the coming years.

For the economies dependent on copper to create wealth, let us hope that this is the case.

This article was originally published in The Citizen on 19 April 2020.