In recent years several countries have seen a tightening of foreign direct investment regulations, giving governments more discretion when scrutinising deals and deciding whether to block or even reverse acquisitions on the grounds of national security. The coronavirus pandemic, forcing many governments to look inwardly at protective measures for their economies, has accelerated this trend.

In recent years several countries have seen a tightening of foreign direct investment regulations, giving governments more discretion when scrutinising deals and deciding whether to block or even reverse acquisitions on the grounds of national security. The coronavirus pandemic, forcing many governments to look inwardly at protective measures for their economies, has accelerated this trend.

On 25 March the EU issued a communiqué to Member States warning that, “among the possible consequences of the current economic shock is an increased potential risk to strategic industries, in particular but by no means limited to healthcare-related industries.”

In addition to the short-term risk of foreign entities acquiring healthcare capacities such as protective equipment or research establishments developing vaccines, many have speculated that in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic Chinese companies may look to take over distressed assets and businesses.

To safeguard strategic aspects of their economies, several governments have been implementing deterrent and protectionist measures to, as one Financial Times commentator put it, “protect their companies from foreign competitors bent on looting and pillaging”. Last month, Spain enacted emergency legislation which included provisions to review non-EU foreign investments, Australia reduced a key takeover threshold from $1.2 billion to zero, and Italian and French leaders have spoken about protecting companies of national interest, if necessary.

Prior to the pandemic, rising national protectionism had driven governments across the globe to strengthen the screening of foreign investment. For instance, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) was given more oversight powers in 2018, the EU published a Regulation in March 2019 which will enhance reviewing mechanisms of FDI, and the UK government announced a new National Security and Investment Bill in December 2019.

Particularly in the context of the US-China trade war, much of the rhetoric surrounding such legislation has been linked to China. There are certainly several examples, most notably in the US, but also in the UK and Europe, of proposed investments and acquisitions by Chinese investors being blocked by the relevant oversight bodies. For instance, earlier this month the UK Government intervened to prevent British graphics chipmaker Imagination Technologies from appointing four new directors with links to China Reform Holdings, a $30bn Chinese government-controlled venture fund. In the United States, CFIUS famously vetoed a deal that had already been completed – forcing Beijing Kunlun Tech to sell its stake in dating app Grindr. CFIUS is still investigating Bytedance’s video sharing app TikTok in relation to its 2017 purchase of Musical.ly.

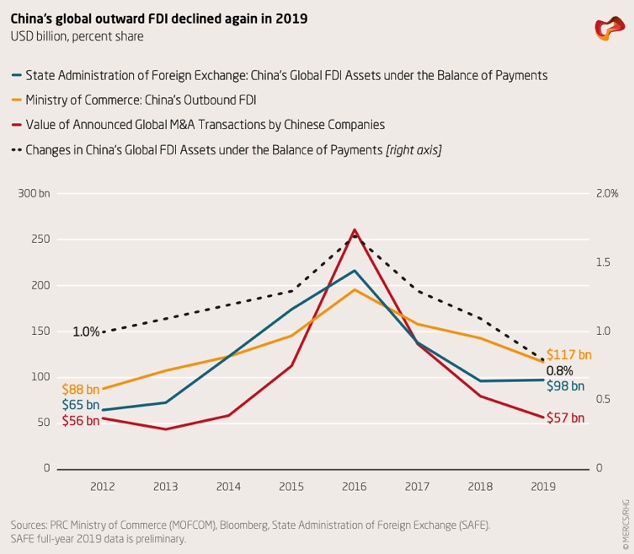

Despite the increase in protectionist rhetoric, China’s foreign investments have been decreasing year on year. As the recent MERICS report, “Chinese FDI in Europe” details, China’s global outbound FDI fell for the third year running in 2019.

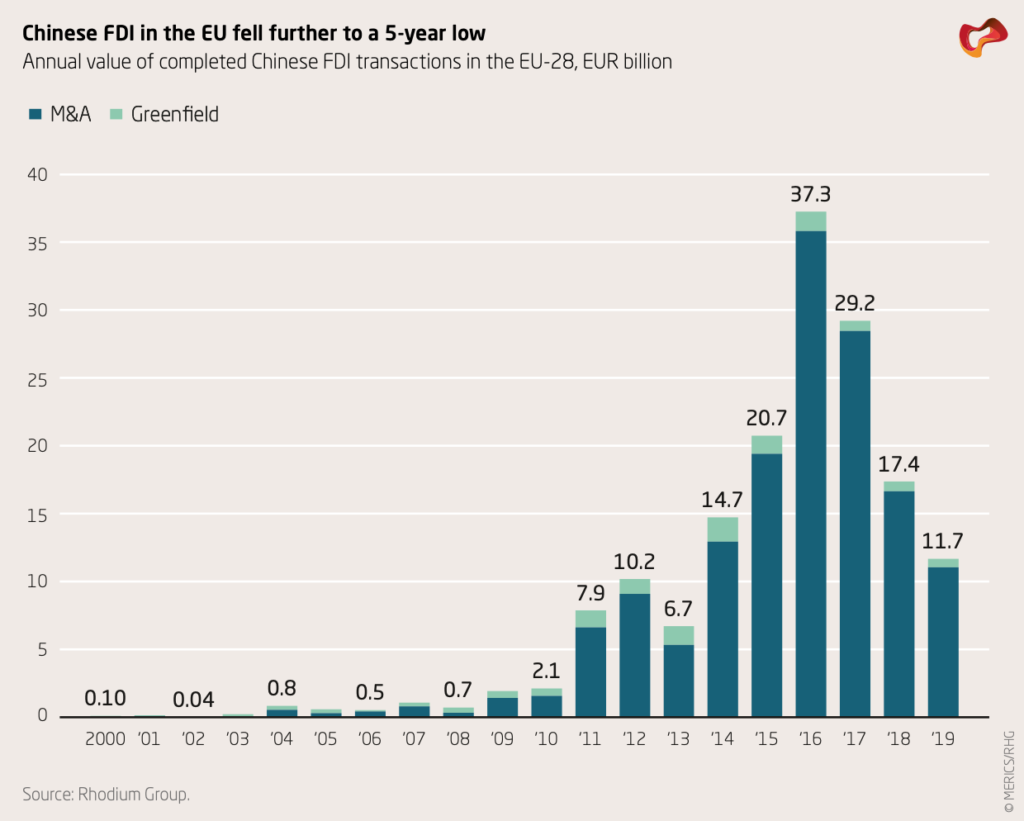

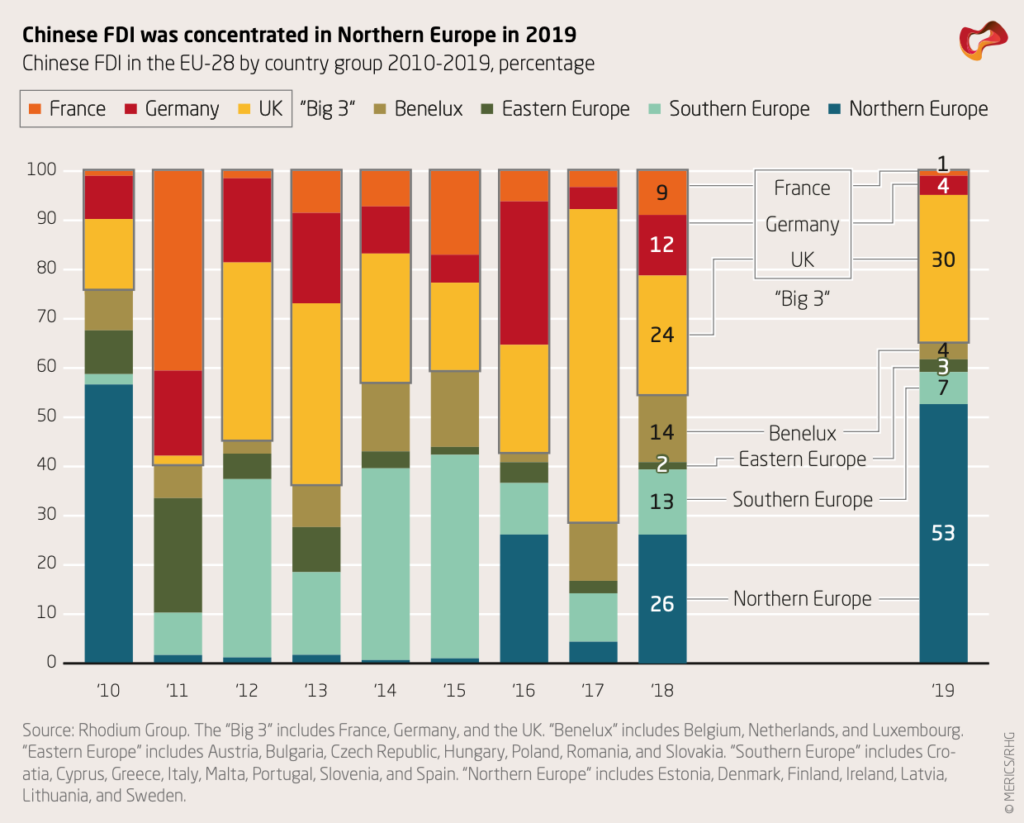

In Europe, the value of completed Chinese FDI transactions dropped 33 per cent from €18bn in 2018 to €12bn in 2019. Chinese investments in the EU reached a peak of €37bn in 2016 and have now returned to volumes similar to 2013 and 2014. MERICS cites three key reasons for the downward trend: regulations imposed by the Chinese government on outbound investment from 2017, a clampdown on a few private individuals pursuing “irrational” investments, and a deleveraging campaign that limited Chinese investors’ ability to finance overseas acquisitions.

It has also been reported that Chinese investment in the US tech sector has sharply declined – between 2018 and 2019 publicly disclosed investments in US start-ups by Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent fell 84 per cent. The worsening climate for Chinese investors, particularly in Silicon Valley, has been linked to lengthy CFIUS approval procedures and fears of bad publicity for companies with significant Chinese investment.

Whilst the overall volume of Chinese investment into Europe may have decreased, an area which has received particular scrutiny on the part of European governments – ICT and tech-related sectors – received the second largest share of investment in 2019 and was the top sector in terms of single transactions, at 20 per cent of all transactions.

In addition to this, whilst equity investments have become more difficult following European countries’ tightening of FDI screening legislation, one area that has received less attention is the potentially problematic research and development collaborations between European and Chinese partners, in the public, private and academic realms.

Although many of these partnerships are beneficial and provide important opportunities to collaborate on global issues, particularly in the contexts of COVID-19 and climate change, R&D collaborations in some cases present risks. For instance, “ones that facilitate the transfer of critical and dual-use technologies to China’s military- industrial complex or contribute to the state’s ability to exert mass control over its population.”

MERICS’ report presents examples that include a University of Warwick collaborative project relating to facial recognition technology, a Queen Mary University collaboration concerning THz technology that the Chinese military is experimenting with in order to develop anti-stealth radars, and a Dublin Institute of Technology partnership with Chengdu’s University of Electronic Science and Technology – a university in China that has been linked to video surveillance projects in Xinjiang.

Protectionist mindsets are sure to continue in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. China’s economic footprint will also continue to broaden, even if at a slower rate than has been seen in recent years. Governments must surely strike an effective balance between protecting national interest and not stifling innovation, collaboration nor competition, particularly in non-sensitive sectors.

Inserted graphics all originate from the Mercator Institute for Chinese Studies (MERICS) and the Rhodium Group’s recent report, “Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update” which is available to download here.